After arriving in New York, Garbo would sit for photographer Arnold Genthe for three different portrait sessions. Their work would transform photography. the first session generated a single standard portrait. The next two sessions would generate fifteen groundbreaking images. Garbo would be the world’s most important portrait photography subject until World War 2.

Garbo had arrived in New York on July 5, 1925. She was on her way to Hollywood and MGM’s immediate objective that July was to turn her letter of intent from January into a full contract. Complications arose and it would be two months before Garbo, and fellow Swede director Mauritz Stiller, would depart New York.

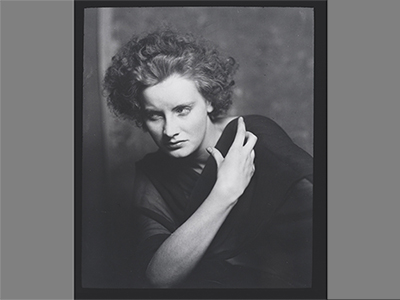

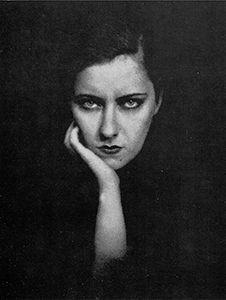

The Arnold Genthe portrait of Greta Garbo from July 21, 1925.

To begin publicity for their new star, MGM set Garbo up with photographers and magazine writers to start the process of building a public image even before she began work in Hollywood. On July 21st Garbo arrived at Genthe’s studio to make a portrait. While Genthe did not work for MGM directly, he would take photographs of film stars as they traveled through New York and place them with magazines. This session produced a single image, which had the notation ‘swan neck’ on the negative sleeve. It was a typical Genthe portrait from that era.

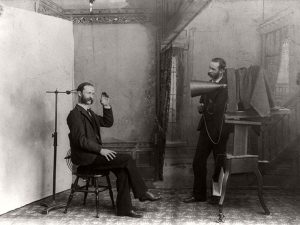

Early photography required long exposures. A stay was often used to hold the subject in place.

Arnold Genthe was one of the important photographers of the early twentieth century. He made beautiful images. Genthe wanted to move away from ridged poses. Early portraits required the sitter to hold still for several seconds because the technology was still primitive. At a time when subjects were posed for portraits, often physically held in place by metal guides, Genthe would put his subjects at ease and capture them in a natural state. He was at the forefront of using new technical innovations in cameras, film and lenses. He wrote about photography as well.

He would donate all of his prints and negatives to the Library of Congress. One can go to the Library of Congress’ website (https://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?co=agc&st=gallery) and all of Genthe’s work is online. Scanning through the images Genthe has generated years of portraits of actors, dancers and wealthy citizens. There is usually one, perhaps two, images from each sitting.

Genthe took this portrait of a posed Norma Shearer in the early 1920s.

This photo of Norma Shearer, from the early 1920s, is a great example of his usual work. She is relaxed. Like most Genthe portrait sessions, the result is just this single image, selected from all of the exposures. Genthe stated in Rebellion in Photography that “something of the soul, the individuality of the sitter, must be expressed in the picture, and furthermore the arrangement of the lines and the distribution of the lights and shades must be managed in such a way as to make a picture of fine artistic merit.”

Anna Duncan dancing for Arnold Genthe at the beach circa 1915.

Genthe also was fascinated by modern dance and took thousands of images of dancers. These images often attempt to capture the emotion and movement of modern dance. Genthe often took these photographs outdoors. For example this image of Anna Duncan was taken at the beach. Many leading photographers of the day found modern dance to be a compelling subject because of the emotional component. Henry Goodwin, who shot Garbo in Sweden before she left for America, and both Nickolas Muray and Edward Steichen, whom would each take several famous photos of Garbo in 1928 all took numerous photos of modern dancers in motion. Isadora Duncan, for one, felt that Genthe did capture what she was trying to express. As Duncan wrote in her autobiography My Life, his; ‘pictures were never photographs of his sitters but his hypnotic imagination of them. He has taken many pictures of me which are not representations of my physical being but representations of conditions of my soul.’

Lejaren à Hiller captures a ‘psychological moment.’

At the same time Lejaren à Hiller was trying to create what he called “the psychological moment” in commercial photographs for his clients. Hiller would spend days trying to create a visual story of the moment a brand was important.

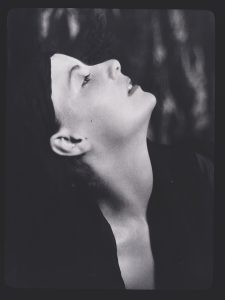

We don’t know what led Garbo to return to Genthe’s studio on July 27th. The result was a stunning set of portraits that were the result of a photographer and subject working to express and capture emotion. Garbo wears a simple black chiffon gown. She folds and drapes it a variety of ways, so it takes a bit of study to realize it is all the same garment. The achievement is not just capturing a single emotive moment, rather the range that Garbo exhibits in the different images. Each images seems to tell a different story and they all deliver visual power.

One of nine images from the July 27, 1925 session with Arnold Genthe.

The images themselves are more like his modern dancer images, with Garbo captured in emotion or motion. A hand is often included expressively. One seems to register her thought. Taken as a group it is clear that the objective was to create a different kind of portrait, one that revealed more than the standard photograph. Garbo achieved this by acting and Genthe knew how to capture the essence of the performance.

Greta Garbo in a pose that emphasizes her throat. Taken July 27, 1925

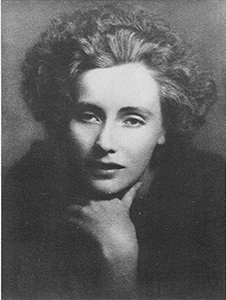

An image of Garbo from the July 31, 1925 session with Arnold Genthe.

It came off so well, Garbo and Genthe did it again on July 31st. This time Garbo’s acting for the camera is more subtle. The images do not strike you as directly as the July 27th portraits, but Garbo’s thoughts still seem to come through to the viewer. After the breakthrough of July 27th, the final session seems to reflect a calibration to deliver Garbo’s thoughts and emotions with more nuance.

Garbo would go on to create stunning portraits with a wide range of photographers, often creating with them their finest portraits. Garbo brought all of her skill and intensity to the studio, and they loved working with her. Portrait photography would never be the same.

While photographs of Garbo had appeared in a few American newspapers from both a 1924 Trianon Studios public relations release and Garbo’s recent arrival in New York, the Genthe image that appeared in the November 1925 issue of Vanity Fair was the first time most Americans had seen Greta Garbo. The image from the July 27th sitting is not the most adventurous or expressive, those would be published later. It was expressive compared to what had been published previously. Photographer and Vanity Fair photo editor Edward Steichen was so intrigued that he tried to mimic the pose with Gloria Swanson in the December issue. The art of acting for the still camera had not yet been understood, so the results are just a shadow of what Garbo and Genthe created.

The Garbo image used in the November 1925 issue of Vanity Fair.

Edward Steichen tried to capture a similar pose by Norma Shearer for the December issue.

Greta Garbo would have been the perfect model for the Pre-rahpaelitesand sculptor Antonio Canova. She was and is the most beautiful woman the world has ever seen.